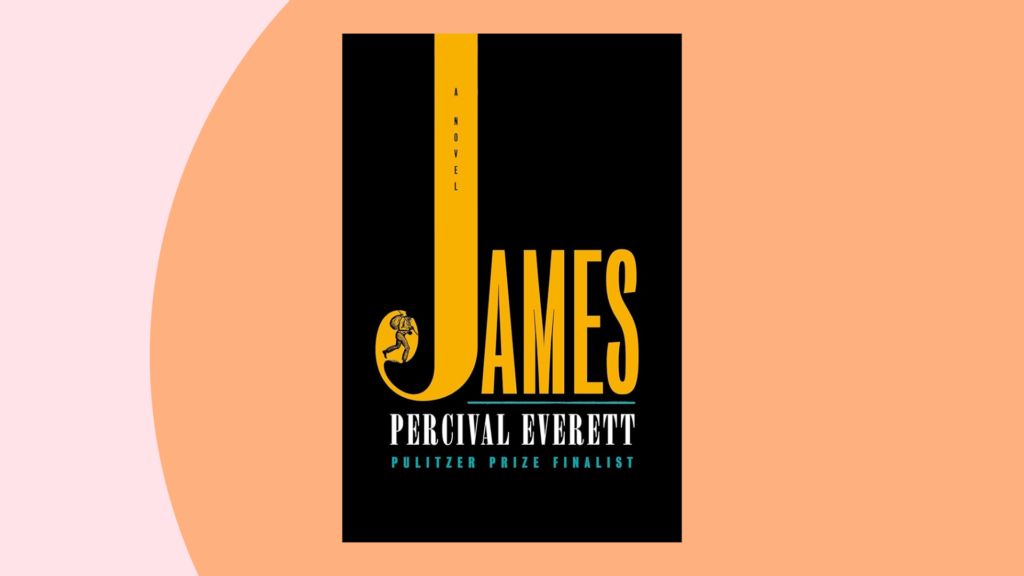

The most impactful work of art I encountered in 2024 is James. Percival Everett’s novel re-presenting the enslaved man first written as Jim in Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain. In Everett’s re-imagining, James is secretly literate, erudite actually, so expert a reader and writer that he teaches his children both high-level English and how to hide that knowledge in front of white people. He is as far from a stereotype as possible. The book has a grand plot twist, but Everett plants genius little seeds along the way. The literary experience of re-seeing a character I’ve “known” since fourth grade mirrors such narrative discoveries in real life.

Most retellings modernize stories but the best ones are corrective. Artists ought to have full support to imagine people we’ve never seen before, but I love retellings that provide explanations that were unavailable, corrupted, or deliberately obscured in the prior work. James is entirely original, as is Jean Rhys’ Wide Sargasso Sea, the 1966 prequel to Jane Eyre that a friend gave me when I was in college. Rhys gives us a postcolonial and feminist view of Antoinette Cosway, the white Creole woman whose suffering starts when Mr. Rochester marries her, renames her “Bertha,” takes her to England, declares her insane, and imprisons her in the attic. He thinks about her, “Creole of pure English descent she may be, but they are not English or European either.” Brontë reduces her to a feral animal; Rhys gives Antoinette back humanity, agency, and dignity.

Reading James reminded me that the possibility of knowing someone better is also available in life and in organizing, maybe even in politics. People I think I know, whether I met them as a toddler or three minutes ago, have ideas, commitments, and reactions that I won’t hear unless I ask, or we spend time together in aimless conversation, or I go to their homes, schools, or workplaces. I didn’t know that one of my closest relatives was pro-choice until I was well into my 30’s. I just assumed she wasn’t based on our other disagreements. Many years ago, I was sitting next to a middle-aged white man, a veteran, on a plane. I told him I was an organizer working on racial justice issues. As I braced for the expected reaction, he declared that it was obvious we didn’t have equality in America, all you had to do was look around at schools, neighborhoods, and prisons. Our relationship ended with the flight, and of course he could have been performing, but regardless it wasn’t the answer I was expecting.

The surprises aren’t always delightful. Our body politic is riven with disappointment in people we thought we knew. Even our more generous assumptions about who holds which values appear to be—in the face of final vote tallies—untrue, or at least less true. The great unfriending that began over morals and politics in 2016 continues to ripple. But nine years and a second Trump victory later, I hope that our openness to each other outpaces our anger. We might find unexpected connections to shift the isolation and distrust that prevent us from finding common cause, enabling demagogues to rule. Reading books like James can expand our imagination for such work.

In James, Everett doesn’t just rewrite Jim—he also rewrites Huck. Although critics like Toni Morrison have recognized Twain’s deep contributions to racial justice narratives, Everett takes Huck on a journey that Twain couldn’t. Times change because people, including artists, change them. Our curiosity, courage, and creativity remain the greatest enablers of mass movements that liberate everyone. As James stays with me, along with Antoinette Cosway, I remember that discovery is a joy, even when the results are sometimes disappointing, and that we always have a chance to tell a new story.